Integration tests aren’t something that should be dreaded. They are an essential part of having your application fully tested.

When talking about testing, we usually think of unit tests where we test a small chunk of code in isolation. However, your application is larger than that small chunk of code and almost no part of your application works in isolation. This is where integration tests prove their importance. Integration tests pick up where unit tests fall short, and they bridge the gap between unit tests and end-to-end tests.

You know you need to write integration tests, so why aren’t you doing it?

In this article, you’ll learn how to write readable and composable integration tests with examples in API-based applications.

While we’ll use JavaScript/

Node.js for all code examples in this article, most ideas discussed can be easily adapted to integration tests on any platform.

Unit Tests vs Integration Tests: You Need Both

Unit tests focus on one particular unit of code. Often, this is a specific method or a function of a bigger component.

These tests are done in isolation, where all external dependencies are typically stubbed or mocked.

In other words, dependencies are replaced with pre-programmed behavior, ensuring that the test’s outcome is only determined by the correctness of the unit being tested.

You can learn more about unit tests

here.

Unit tests are used to maintain high-quality code with good design. They also allow us to easily cover corner cases.

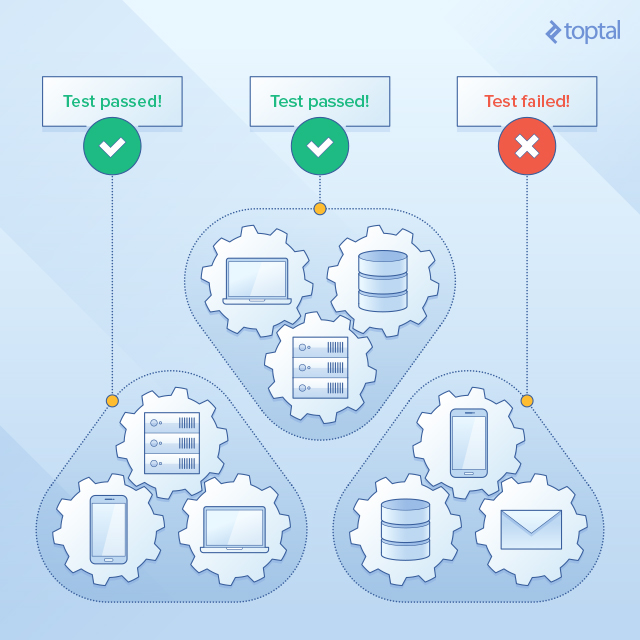

The drawback, however, is that unit tests can’t cover the interaction between components. This is where integration tests become useful.

Integration Tests

If unit tests are defined by testing the smallest units of code in isolation, then integration tests are just the opposite.

Integration tests are used to test multiple, bigger units (components) in interaction, and can sometimes even span multiple systems.

The purpose of integration tests is to find bugs in the connections and dependencies between various components, such as:

- Passing invalid or incorrectly ordered arguments

- Broken database schema

- Invalid cache integration

- Flaws in business logic or errors in data flow (because testing is now done from broader view).

If the components we’re testing don’t have any complicated logic (e.g. components with minimal

cyclomatic complexity), integration tests will be far more important than unit tests.

In this case, unit tests will be used primarily to enforce a good code design.

While unit tests help ensure that functions are properly written, integration tests help ensure that the system is working properly as a whole. So both unit tests and integration tests each serve their own complementary purpose, and both are essential to a comprehensive testing approach.

Unit tests and integration tests are like two sides of the same coin. The coin is not valid without both.

Therefore, testing isn’t complete until you’ve completed both integration and unit tests.

Set up the Suite for Integration Tests

While setting up a test suite for unit tests is pretty straightforward, setting up a test suite for integration tests is oftentimes more challenging.

For example, components in integration tests can have dependencies that are outside the project, like databases, file systems, email providers, external payment services, and so on.

Occasionally, integration tests need to use these external services and components, and sometimes they can be stubbed.

When they are needed, it can lead to several challenges.

- Fragile test execution: External services can be unavailable, return an invalid response, or be in an invalid state. In some cases, this may result in a false positive, other times it may result in a false negative.

- Slow execution: Preparing and connecting to external services can be slow. Usually, tests are run on an external server as a part of CI.

- Complex test setup: External services need to be in the desired state for testing. For example, the database should be preloaded with the requisite test data, etc.

Directions To Follow While Writing Integration Tests

Integration tests don’t have strict rules like

unit tests. Despite this, there are some general directions to follow when writing integration tests.

Repeatable Tests

Test order or dependencies shouldn’t alter the test result. Running the same test multiple times should always return the same result. This can be difficult to achieve if the test is using the Internet to connect to third-party services. However, this issue can be worked around through stubbing and mocking.

For external dependencies that you have more control over, setting up steps before and after an integration test will help ensure that the test is always run starting from an identical state.

Testing Relevant Actions

To test all possible cases, unit tests are a far better option.

Integration tests are more oriented on the connection between modules, hence testing

happy scenarios is usually the way to go because it will cover the important connections between modules.

Comprehensible Test and Assertion

One quick view of the test should inform the reader what is being tested, how the environment is setup, what is stubbed, when the test is executed, and what is asserted. Assertions should be simple and make use of helpers for better comparison and logging.

Easy Test Setup

Getting the test to the initial state should be as simple and as understandable as possible.

Avoid Testing Third-Party Code

While third-party services may be used in tests, there’s no need to test them. And if you don’t trust them, you probably shouldn’t be using them.

Leave Production Code Free of Test Code

Relevant Logging

Failed tests aren’t very valuable without good logging.

When tests pass, no extra logging is needed. But when they fail, extensive logging is vital.

Logging should contain all database queries, API requests and responses, as well as a full comparison of what is being asserted. This can significantly facilitate debugging.

Good Tests Look Clean and Comprehensible

A simple test that follows the guidelines herein could look like this:

const co = require('co');

const test = require('blue-tape');

const factory = require('factory');

const superTest = require('../utils/super_test');

const testEnvironment = require('../utils/test_environment_preparer');

const path = '/v1/admin/recipes';

test(`API GET ${path}`, co.wrap(function* (t) {

yield testEnvironment.prepare();

const recipe1 = yield factory.create('recipe');

const recipe2 = yield factory.create('recipe');

const serverResponse = yield superTest.get(path);

t.deepEqual(serverResponse.body, [recipe1, recipe2]);

}));

The code above is testing an API (GET /v1/admin/recipes) that expects it to return an array of saved recipes as a response.

You can see that the test, as simple as it may be, relies on a lot of utilities. This is common for any good integration test suite.

Helper components make it easy to write comprehensible integration tests.

Let’s review what components are needed for integration testing.

Helper Components

A comprehensive testing suite has a few basic ingredients, including: flow control, testing framework, database handler, and a way to connect to backend APIs.

Flow Control

One of the biggest challenges in JavaScript testing is the asynchronous flow.

Callbacks can

wreak havoc in code and promises are just not enough. This is where flow helpers become useful.

While waiting for

async/await to be fully supported, libraries with similar behavior can be used. The goal is to write readable, expressive, and robust code with the possibility of having async flow.

Co enables code to be written in a nice way while it keeps it non-blocking. This is done through defining a co generator function and then yielding results.

Another solution is to use

Bluebird. Bluebird is a promise library that has very useful features like handling of arrays, errors, time, etc.

Co and Bluebird coroutine behave similarly to async/await in ES7 (waiting for resolution before continuing), the only difference being that it will always return a promise, which is useful for handling errors.

Testing Framework

Choosing a test framework just comes down to personal preference. My preference is a framework that is easy to use, has no side effects, and which output is easily readable and piped.

There’s a wide array of testing frameworks in JavaScript. In our examples, we are using

Tape. Tape, in my opinion, not only fulfills these requirements, but also is cleaner and simpler than other test frameworks like Mocha or Jasmin.

TAP has variations for most programming languages.

Tape takes tests as an input, runs them, and then outputs results as a TAP. The TAP result can then be piped to the test reporter or can be output to the console in a raw format. Tape is run from the command line.

Tape has some nice features, like defining a module to load before running the entire test suite, providing a small and simple assertion library, and defining the number of assertions that should be called in a test. Using a module to preload can simplify preparing a test environment, and remove any unnecessary code.

Factory Library

A factory library allows you to replace your static fixture files with a much more flexible way to generate data for a test. Such a library allows you to define models and create entities for those models without writing messy, complex code.

const factory = require('factory-girl').factory;

const User = require('../models/user');

factory.define('user', User, { username: 'Bob', number_of_recipes: 50 });

const user = factory.build('user');

To start, a new model must be defined in factory_girl.

It’s specified with a name, a model from your project, and an object from which a new instance is generated.

Alternatively, instead of defining the object from which a new instance is generated, a function can be provided that will return an object or a promise.

When creating a new instance of a model, we can:

- Override any value in the newly generated instance

- Pass additional values to the build function option

Let’s see an example.

const factory = require('factory-girl').factory;

const User = require('../models/user');

factory.define('user', User, (buildOptions) => {

return {

name: 'Mike',

surname: 'Dow',

email: buildOptions.email || 'mike@gmail.com'

}

});

const user1 = factory.build('user');

const user2 = factory.build('user', {name: 'John'}, {email: 'john@gmail.com'});

Connecting to APIs

Starting a full-blown HTTP server and making an actual HTTP request, only to tear it down a few seconds later – especially when conducting multiple tests – is totally inefficient and may cause integration tests to take significantly longer than necessary.

SuperTest is a JavaScript library for calling APIs without creating a new active server. It’s based on SuperAgent, a library for creating TCP requests. With this library, there is no need to create new TCP connections. APIs are almost instantly called.

SuperTest, with support for promises, is

supertest-as-promised. When such a request returns a promise, it lets you avoid multiple nested callback functions, making it far easier to handle the flow.

const express = require('express')

const request = require('supertest-as-promised');

const app = express();

request(app).get("/recipes").then(res => assert(....));

SuperTest was made for the Express.js framework, but with small changes it can be used with other frameworks as well.

Other Utilities

In some cases, there’s a need to mock some dependency in our code, test logic around functions using spies, or use stubs at certain places. This is where some of these utility packages come in handy.

SinonJS is a great library that supports spies, stubs, and mocks for tests. It also supports other useful testing features, like bending time, test sandbox, and expanded assertion, as well as fake servers and requests.

In some cases, there is a need to mock some dependency in our code. References to services that we would like to mock are used by other parts of the system.

To resolve this problem, we can use

dependency injection or, if that is not an option, we can use a mocking service like Mockery.

Mockery helps mocking code that has external dependencies. To use it properly, Mockery should be called before loading tests or code.

const mockery = require('mockery');

mockery.enable({

warnOnReplace: false,

warnOnUnregistered: false

});

const mockingStripe = require('lib/services/internal/stripe'); mockery.registerMock('lib/services/internal/stripe', mockingStripe);

With this new reference (in this example, mockingStripe), it is easier to mock services later in our tests.

const stubStripeTransfer = sinon.stub(mockingStripe, 'transferAmount');

stubStripeTransfer.returns(Promise.resolve(null));

With the help of Sinon library, it is easy to mock. The only problem here is that this stub will propagate to other tests. To sandbox it, the sinon sandbox can be used. With it, later tests can bring the system back to its initial state.

const sandbox = require('sinon').sandbox.create();

const stubStripeTransfer = sandbox.sinon.stub(mockingStripe, 'transferAmount');

stubStripeTransfer.returns(Promise.resolve(null));

sandbox.restore();

There is a need for other components for functions like:

- Emptying the database (can be done with one hierarchy pre-build query)

- Setting it to working state (sequelize-fixtures)

- Mocking TCP requests to 3rd party services (nock)

- Using richer assertions (chai)

- Saved responses from third-parties (easy-fix)

Not-so-simple Tests

Abstraction and extensibility are key elements to building an effective integration test suite. Everything that removes focus from the core of the test (preparation of its data, action and assertion) should be grouped and abstracted into utility functions.

Although there is no right or wrong path here, as everything depends on the project and its needs, some key qualities are still common to any good integration test suite.

The following code shows how to test an API that creates a recipe and sends an email as a side-effect.

It stubs the external email provider so that you can test if an email would have been sent without actually sending one. The test also verifies if the API responded with the appropriate status code.

const co = require('co');

const factory = require('factory');

const superTest = require('../utils/super_test');

const basicEnv = require('../utils/basic_test_enivornment');

const path = '/v1/admin/recipes';

basicEnv.test(`API POST ${path}`, co.wrap(function* (t, assert, sandbox) {

const chef = yield factory.create(‘chef’);

const body = {

chef_id: chef.id,

recipe_name: ‘cake’,

Ingredients: [‘carrot’, ‘chocolate’, ‘biscuit’]

};

const stub = sandbox.stub(mockery.emailProvider, 'sendNewEmail').returnsPromise(null);

const serverResponse = yield superTest.get(path, body);

assert.spies(stub).called(1);

assert.statusCode(serverResponse, 201);

}));

The test above is repeatable as it starts with a clean environment every time.

It has a simple setup process, where everything related to the setup is consolidated inside the basicEnv.test function.

It tests only one action - a single API. And it clearly states the test’s expectations through simple assert statements. Also, the test doesn’t involve third-party code by stubbing/mocking.

Start Writing Integration Tests

When pushing new code to production, developers (and all other project participants) want to be sure that new features will work and old ones won’t break.

This is very hard to achieve without testing, and if done poorly can lead to frustration, project fatigue, and eventually project failure.

Integration tests, combined with unit tests, are the first line of defense.

Using only one of the two is insufficient and will leave a lot of space for uncovered errors. Always utilizing both will make new commits robust, and deliver confidence and inspire trust in all project participants.